This lesson introduces the shell, also known as the command line. There are many different shells: We are using the bash shell.

An optional lesson on more advanced intermediate shell features is also available for you if you are interested.

Table of contents

Background and Motivation

As a computational scientist you have one primary tool at your hand: a computer. And like an experimental scientist, you will have to be able to interact with it, adjust it, tweak it, fix it, and generally make it do things that it has never done before.

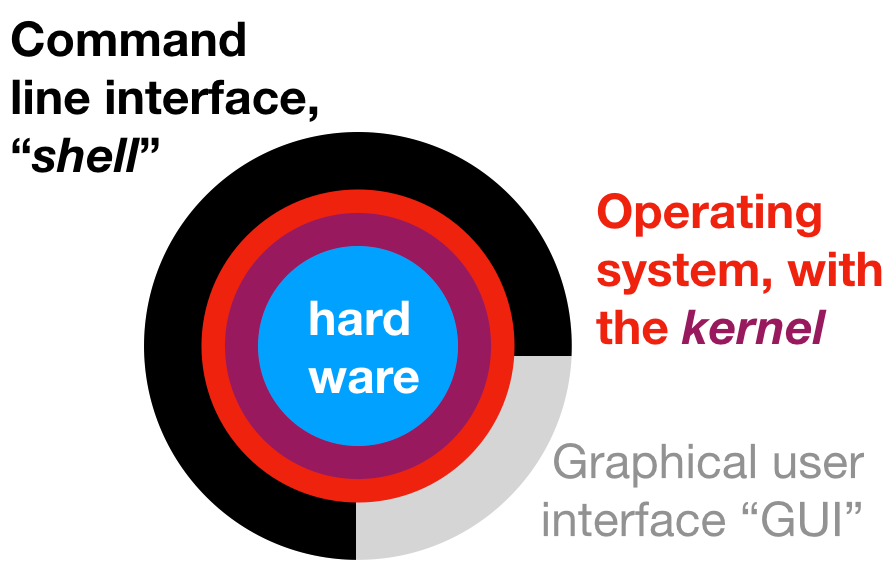

You are probably used to interacting with a computer via a graphical user interface (“GUI”) — windows, browsers, a mouse or touch screen. Although convenient, this limits you to the interactions designed into the interface. To get more out of a machine you have to talk to it more directly.

We will interact with the computer using the text-based terminal through a so-called command line interface (CLI). The user types input commands; the commands are read, executed, and output is printed. The program responsible for doing this is called the shell (because it “encloses” the operating system to simplify user interaction with it).

The shell is a program like any other but it’s primary purpose is to run other programs; most of the input “commands” are in fact other programs. The shell is very good at working with the file system (files and directories), combining multiple existing tools in powerful ways, and automating tasks. On a Unix-like operating systems (typically used for high-performance computing) using the shell is a very powerful (and essential) way to interact with the computer.

Introductory Shell Tutorial

Accessing the shell

On a typical Linux system you open an application called terminal or xterm or kterm (or similar).

On macOS you open Terminal.app (in the Utilities folder in Applications).

On Windows we use Git Bash: Find it in the Program menu under All Programs/Git/Git Bash

Shell prompt

You should be greeted by the prompt, which can look like this

$

with the cursor as an underline or block showing that you can type. Often your prompt is more elaborate, e.g.

dvader@deathstar.empire.gov ~$

Executing commands

Commands are executed by typing the name of the command (typically an abbreviated English word like cd for “change directory”, ls for “list”, but also python for the Python interpreter) and then finishing with return (or enter).

Type

whoamiand hit enter. You should see your username being printed to the screen.

Type

cdand hit enter to begin the lesson. From now on, input will just be shown and you should enter it.

General syntax of a shell command

Commands generally take arguments (what to operate on, required) and options (modify the standard behavior, optional).

command_name -v -o optarg --long-opt arg1 arg2Often, omitting the argument also works and a default is assumed. You can learn more about commands with the help function (try running just with option -h or --help or on Linux/macOS, man command_name; the Git Bash installation does not come with man pages but you can use services on the web such as the Debian man pages).

Navigating Files and Directories

The operating system manages access to files and directories in the file system (typically, the stuff that you see on your disk).

- files = documents, data, pictures, …

- directory = “folder”; may contain any number of files or other directories

Instead of using your graphical File Explorer or Finder we want to use shell commands to

- move around the file system

- get information about files and directories

- specify the location of files and directories

Commands

pwd(print working directory)ls(list directory)cd(change directory)

Paths

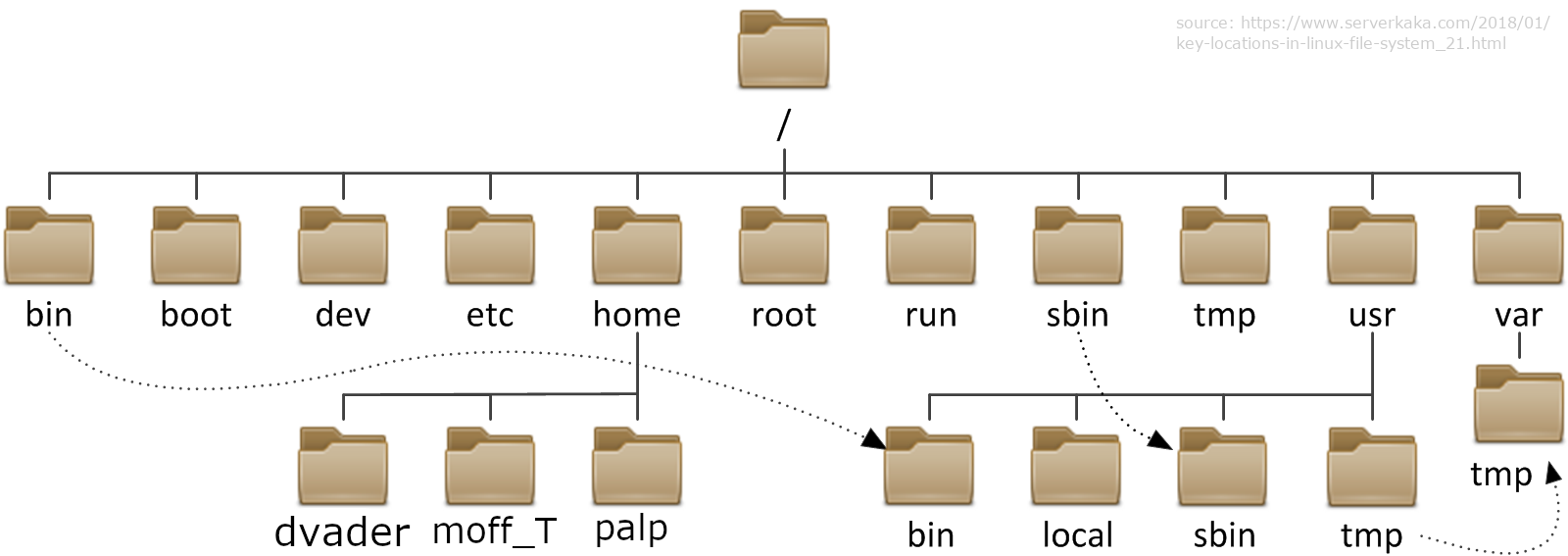

A path consists of directory names separated by forward-slashes “/” and possibly a final file name.

/(the actual name of the “root” directory)/home/dvaderor/Users/dvader/usr/bin/nanobooks.txt/home/dvader/Documents/deathstar/weaknesses.pdfDocuments/deathstar/weaknesses.pdf

Paths starting with / are called absolute paths; anything else is a relative path, starting from the current working directory (check with pwd).

Special directory names:

.is the current directory (e.g.,./Documents)..is the parent directory (e.g.,../../home/dvader/..)~is the home directory (only when leading the path, e.g.,~/Documents)

Location in the files system: pwd

Assume user dvader has the following directory layout in his home directory /home/dvader 1:

/home/dvader/

Documents/

deathstar/

weaknesses.pdf

electrical_bill.dat

work/

data/

planets.dat

bases

When Mr Vader logs in he starts in his home directory, /home/dvader. He can run pwd to “print the working directory”:

pwdwhich shows /home/dvader.

Activity Find Your Home

- Open Terminal

- Type

pwd

and hit enter. Note the directory name: this is your home directory.

- share your home directory name (show your neighbor or copy and paste into the chat)

Listing file system contents: ls

If he executes ls (“list”) he will see something like

Documents

data

Activity List Your Home directory

- open a terminal (or use the open terminal from the last exercise)

- Type

ls

- Compare the files that you see with those of your neighbor (show or copy and paste into the chat)

Moving around the file system: cd

If he executes the cd command

cd /home/dvader/Documents/deathstarthen he will have moved to the deathstar directory; confirm with pwd!:

pwdwill print

/home/dvader/Documents/deathstar

If he runs

lshe will see

electrical_bill.dat weaknesses.pdf

The cd command took an argument, the directory to go to.

Activity Going up

- Go to the parent directory of your home dir:

cd ..

- List the contents

ls

Activity Going Home

- Type

cd

- Where are you now? (What command can you use to print the directory that you’re in?)

More on cd

The command cd on its own always returns you to your home directory. (It is equivalent to cd ~.)

In order to get to the data directory he could use the command cd /home/dvader/data but instead he uses the special directory .. (which means “the directory above this one”):

cd ../../dataA second special directory is . (“this directory”). . and .. are understood by all commands.

Autocompletion

- Use the

TABkey while typing: autocompletion is one of the best features of the shell! Pro Tip! - The other great interactive feature is the history: try using the cursor-up and -down keys. Pro Tip!

Wildcards

The shell contains a simple pattern matching syntax (wildcards or “glob patterns”) to select all files that match the pattern. Commonly used patterns are

*: matches zero or more characters in a name, e.g.,*.datmatches all files ending in.dat, andreport_2021-*.txtmatchesreport-2021-11.txt,report-2021-12.txt, but notreport-2020-2.txt?matches a single character in a name, e.g.,?.jpgmatches1.jpg,a.jpg, but notab.jpg

Neither of them matches a leading . in a file name or a space or the directory separator /.

Example: List all dat files

List all “dat” files in the current directory: Use the character * to match “any part of a file name”

ls *.datExample: List all commands with “oo” in their name

List all files containing “oo” in the /usr/bin directory (will only work on Linux or macOS):

ls /usr/bin/*oo*Example: Delete jpg files in directories 19xx

Warning

DO NOT COPY AND PASTE ANY COMMAND LINE CONTAINING rm WITHOUT THINKING TWICE ABOUT IT. You have been warned.

Delete all jpg images in directories from the last century

rm Pictures/19??/*.jpg(Note that 19?? matches anything that looks like a year from the last century such as 1999, 1969, … although it would also match 19xy; the *.jpg pattern matches all files with suffix jpg.)

Example: Show all two-letter Unix commands

Show commands with exactly two letters (assuming that you have a Unix-like OS such as Linux or macOS where the commands are located in /bin and /usr/bin):

ls /bin/?? /usr/bin/??(Two letter commands are important — learn more about these commands, e.g., with the three-letter command man.)

Example: Copy Jupyter notebooks to another directory

As part of working with code in this class, we will have to copy Jupyter notebooks from one directory to another directory

cp ~/PHY432-resources/10_ODEs/*.ipynb ~/PHY432/10_ODEs/Error messages

Unix commands are terse: If everything works, they say nothing. If they fail, you get a short (sometimes cryptic) error message.

Try

cd bogusThis gives

bash: cd: bogus: No such file or directory

Warning

Always read error messages!

Activity Explore your file system

- What does the following sequence of commands show?

cd ls -a Go to the

bindirectory that is located in the root directory (at least on Linux and macOS, this would be/bin) or to the anaconda distribution’sbindirectory (e.g.,~/Anaconda3/bin) (on Windows).- List the files there.

- Did you find “cp” and “grep” and also “ls”?

If you cannot find any of these

bindirectories run the commandwhich lswhich should display something like

/PATH/TO/lswhere “/PATH/TO” is the directory that contains thelscommand. Use that directory as thebin-directory to investigate.- What does

ls -R /show? (Try^C, i.e., press CONTROL and C at the same time…) - Try other options of

lssuch as-shor-sha. — asklsfor help! - Is there a difference between

ls -sha,ls -ash, andls -a -s -h?

Tips to make your (shell) life easy

- Use the shell’s convenience features:

TABcompletion Pro Tip!- up/down arrow to get commands that you already typed. Pro Tip!

historyshows all the commands you typed so far- Try out

Control+R(^R) to search through your shell history. ^Aand^Ewill likely take you to the beginning and end of a line

- Use

cd ..to go up,cd ../..to go up twice etc. - Use

cd -to go to the previous directory I was in (only works forcd). - Use the tilde character

~for your home directory, e.g.cd ~/Documentsis equivalent tocd /home/dvader/Documents. - Use wildcards (

*) but test them withlsbefore using them withrm!

Creating directories and files

We want to

- create, copy, rename, and delete files and directories

- edit text files

Commands

mkdir(make directory)- your editor of choice (Visual Studio Code by default for the class,

nanois an alternative choice 2)

Activity Directory structure for the class

Make a directory PHY432 in your home directory for the class and inside it, one called 01_shell for today’s lesson, using the following sequence of shell commands:

cd ~

mkdir PHY432

cd PHY432

mkdir 01_shellNote:

- Avoid spaces and most special characters in file names. All letters and numbers together with underscore

_, minus sign-, and period.are ok. 3 Pro Tip! - Plain

mkdircannot create multiple directories deep in one go unless you have the-poption available (check!).

Activity Create Documents/work

- Inside your

01_shelldirectory, create three directories,dataandDocuments/work. - Go to

Documents/work

Creating text files with a text editor

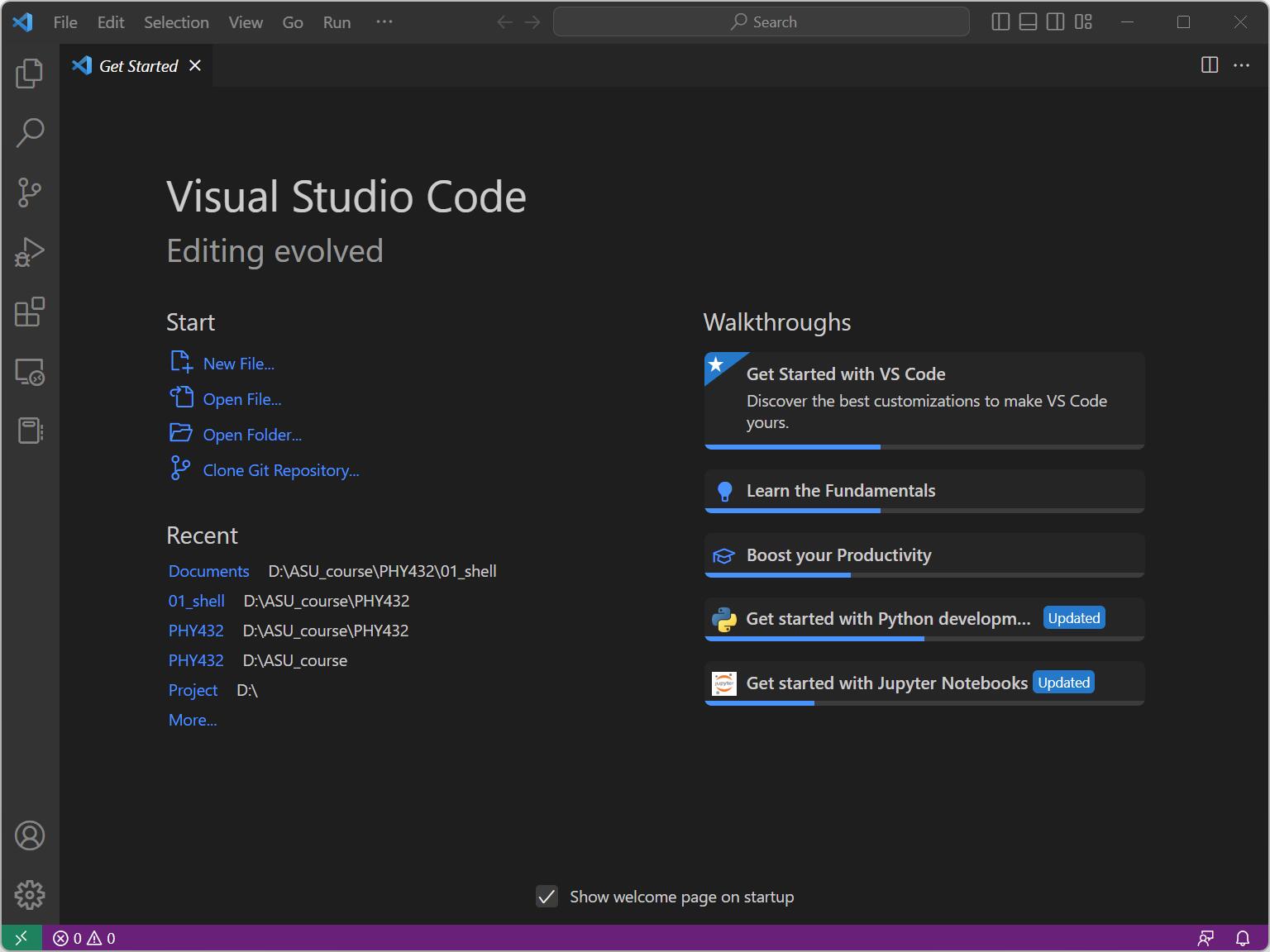

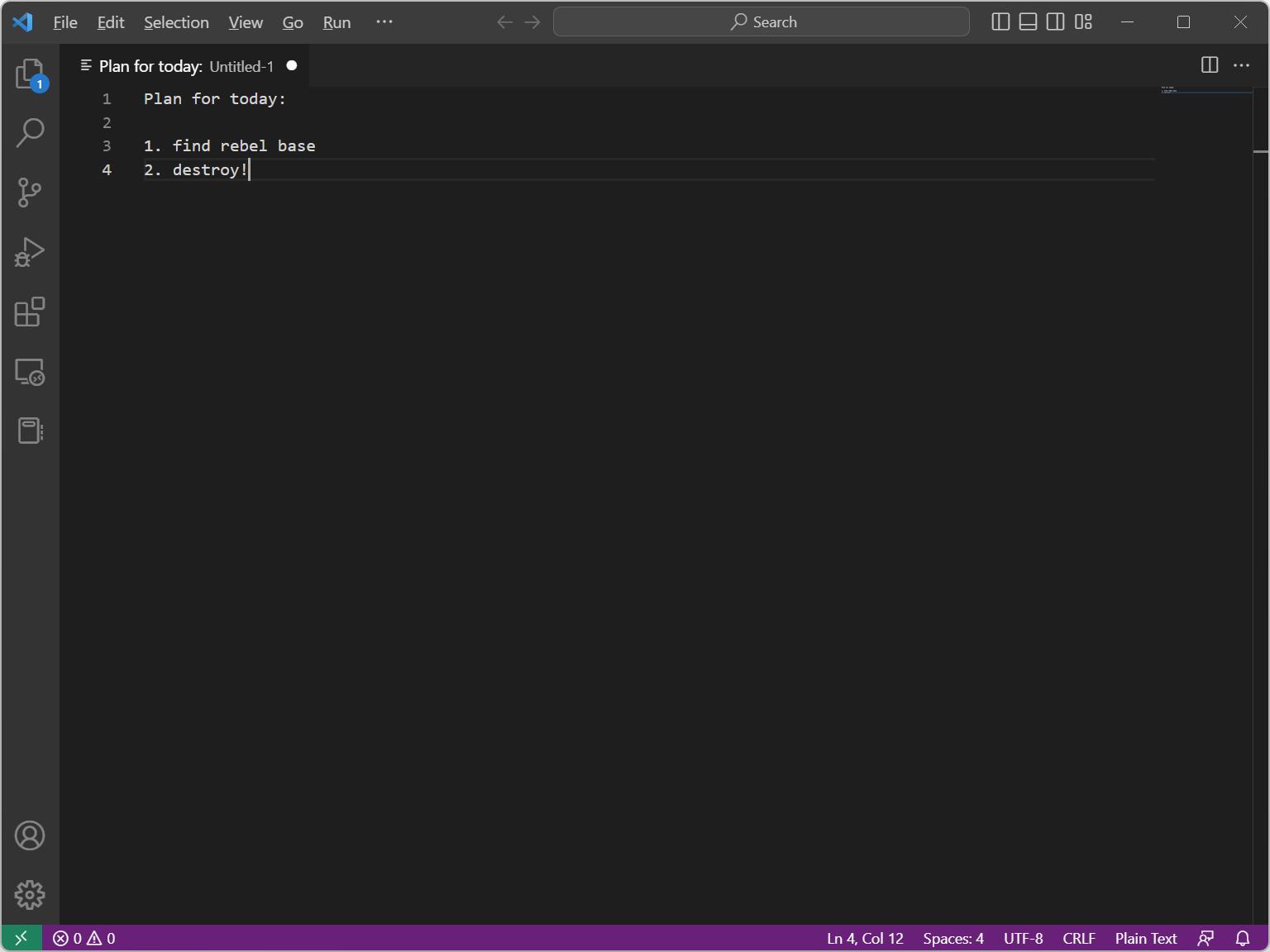

Run Visual Studio Code by either launching it from a menu or from the commandline 4

codeYou should see something like this:

We will now create a TODO list in a file with name TODO and content

Plan for today:

1. find rebel base

2. destroy!

Open a new file via the menu option

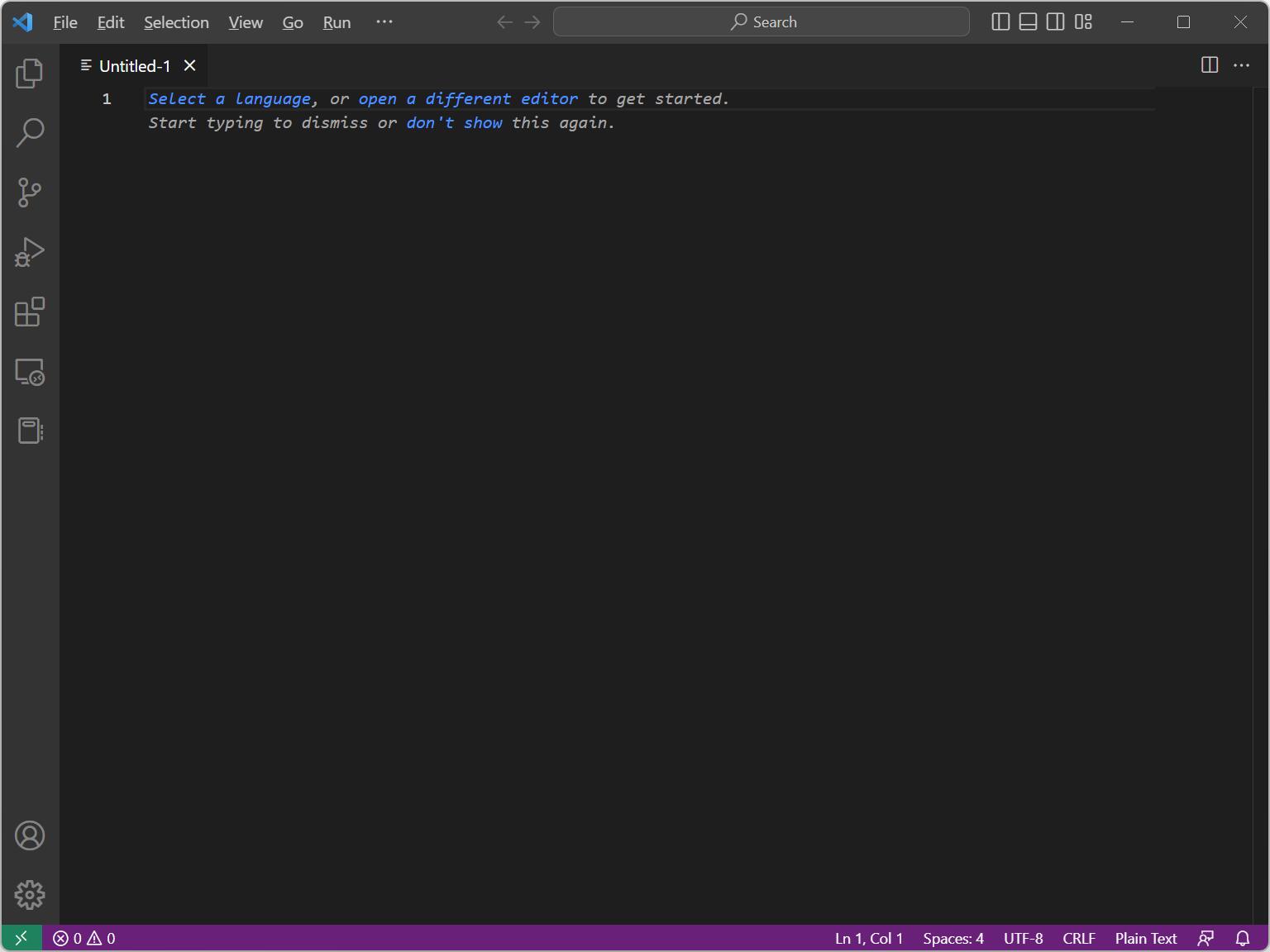

File → New File

You should have a tab named Untitled-1.

Close all the other tabs. It should look like this:

Type the todo list into the editor window.

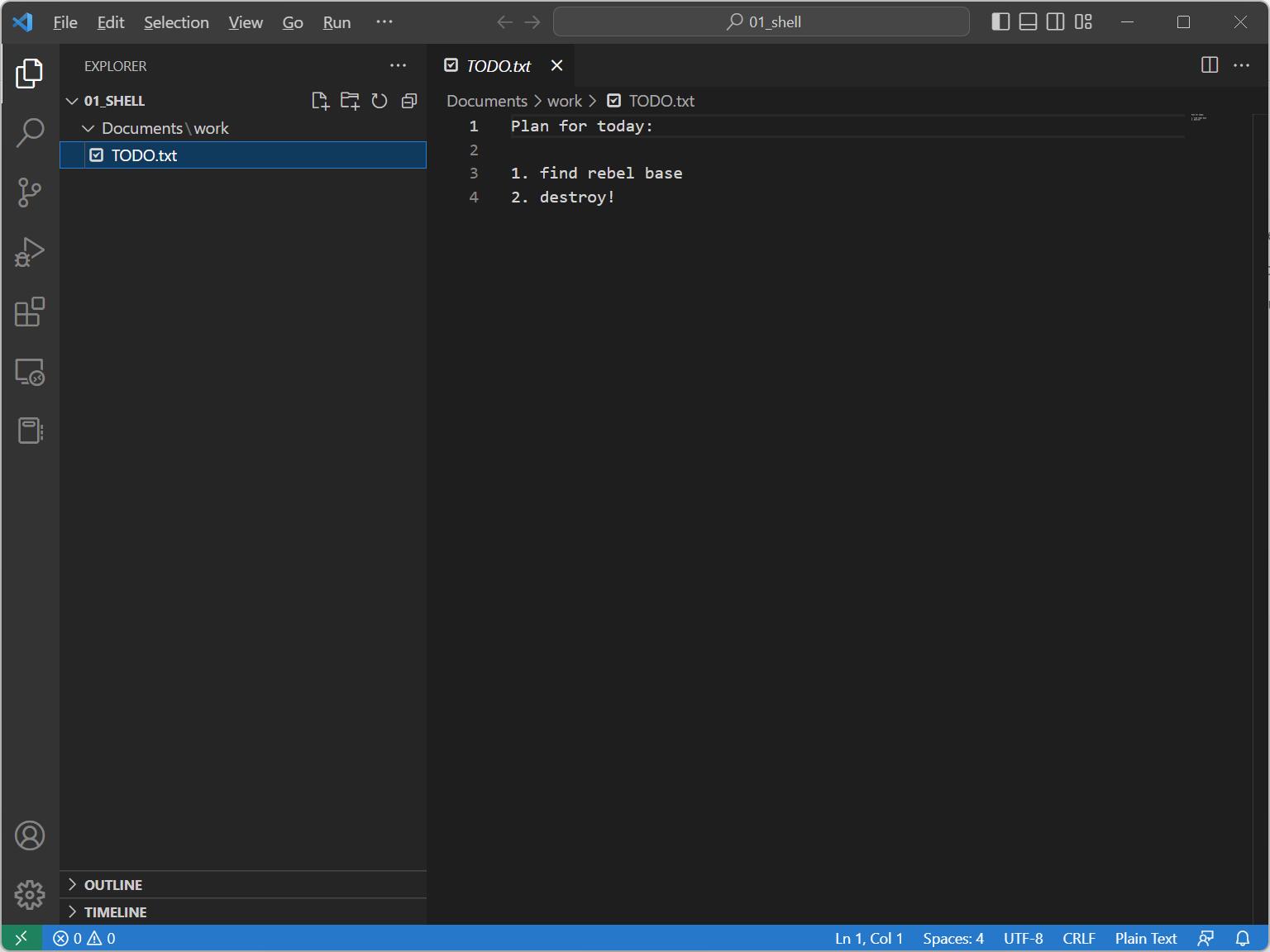

Save it to file with name ‘TODO’ with menu option

File → Save

Make sure to navigate to your the

PHY432/01_shell/Documents/workdirectory.

You can hide the “project” view with the directory structure.

Quit Visual Studio Code (details depend on your operating system; find the Exit menu option either under File.

Check that the file is in the directory with

ls.

You can re-open the file from the command line 4:

code TODO(Alternatively, open Visual Studio Code from your GUI and find the file TODO through the File → Open file dialog.)

Activity Create a file with your editor

Create a file

~/PHY432/Documents/work/lesson.txtwith three lessons from today:1. computers are tools 2. the shell is powerfull 3. basic shell commands: pwd, cd, lssave the file and check that it is there with

ls -l ~/PHY432/Documents/work/lesson.txt

- Open the file again and add a 4th lesson regarding file editing.

Copy, rename, delete

cp(copy file,cp -rcopy recursively, including directories)mv(move, i.e. rename, also to another directory)rmdir(remove empty directory)rm(remove file,rm -rremove recursively (dangerous!))WARNING

There is no “Trashcan” or built in backup. Once you

rmsomething, it is gone. Be especially careful withrm -r.rmalso has the force (-f) option to ignore any safeguards such as permission settings that would otherwise not let you write to or delete a file.WARNING

Do not execute

rm -rf *. It will erase everything permanently.

Pro Tip

All these commands can also work on multiple filenames.

Homework Activity

This is a more extended exercise in using various shell commands. With the previous examples you should have a directory tree that looks like this:

PHY432/

└── 01_shell

├── Documents

│ └── work

│ ├── TODO

│ └── lesson.txt

└── data

Starting from this directory structure, perform the following file system manipulations:

- Make a backup (call it

TODO.bak) of the TODO list with thecpcommand. - Rename

TODOtoTODO.txtwith themvcommand. Make a directory

notesunder thedatadirectory: You should now have a directory tree similar toPHY432/ └── 01_shell ├── Documents │ └── work │ ├── TODO.bak │ ├── TODO.txt │ └── lesson.txt └── data └── notesCheck with

ls -R ~/PHY432(ortree ~/PHY432)- Put a copy of

TODO.txtinto thenotesdirectory (usingcp). - Create a new text file

data/notes/hints.txtand write any hints for possible rebel bases into this file. - Open

notes/TODO.txtin Visual Studio Code and add a note to item 1 too look in thehints.txtfile. Save and exit. Make a copy of your

notesdirectory in your work directory. Your tree should now look like this:PHY432/ └── 01_shell ├── Documents │ └── work │ ├── TODO.bak │ ├── TODO.txt │ ├── lesson.txt │ └── notes │ ├── TODO.txt │ └── hints.txt └── data └── notes ├── TODO.txt └── hints.txt- Remove

data/notes/hints.txtwithrm. - Remove

data/noteswithrmdir. 5 - Move

Documents/work/notes/hints.txtinto theworkdirectory. - Remove the useless

Documents/work/notesdirectory withrm -r(careful !)

Credits

This lesson builds on An Introduction to the command line with Unix Basics and the Software Carpentry lesson on The Unix Shell.

Footnotes

You can also see if you have the

treecommand installed, which shows you beautiful directory trees:$ tree ~dvader /home/dvader/ ├── Documents │ ├── deathstar │ │ ├── electrical_bill.dat │ │ └── weaknesses.txt │ └── work └── data ├── bases └── planets.dattreeis typically not included with git-bash. ↩Upgrading nano: If you are using

nanoas your editor then you want to enable a few useful features including syntax highlighting. The easiest way is to download the config files as the zip file nanoconfig.zip and unpack them in your home directory (curlcan be used to download a file directly instead of having to use the browser):cd curl https://py4phy.github.io/PHY432/assets/resources/nanoconfig.zip -O unzip nanoconfig.zipThis should create the file

~/.nanorc(which you can edit to customize further) and the directory~/.nano. ↩If you must need spaces then enclose the string in single or double quotes, e.g.,

'/c/Program Files/'or"/c/Program Files". Double quotes admit shell variable expansions, single quotes do not. Note that a tilde~within quotes will not expand to the home directory! ↩If you cannot start

codefrom the commandline, go back to Setting up the Environment: Testing: editor (Visual Studio Code) and follow the steps described there. ↩ ↩2Or rather, attempt to remove the directory. This command should fail for this exercise. If you wanted to really remove the directory, which command would you need to use? ↩