Everything in Python is an object. Objects are a more general approach to “packaging code into re-usable units”.

Table of contents

We are continuing from the previous lesson in the “work directory” ~/PHY432/03_python. We will use ipython and your text editor.

Introduction

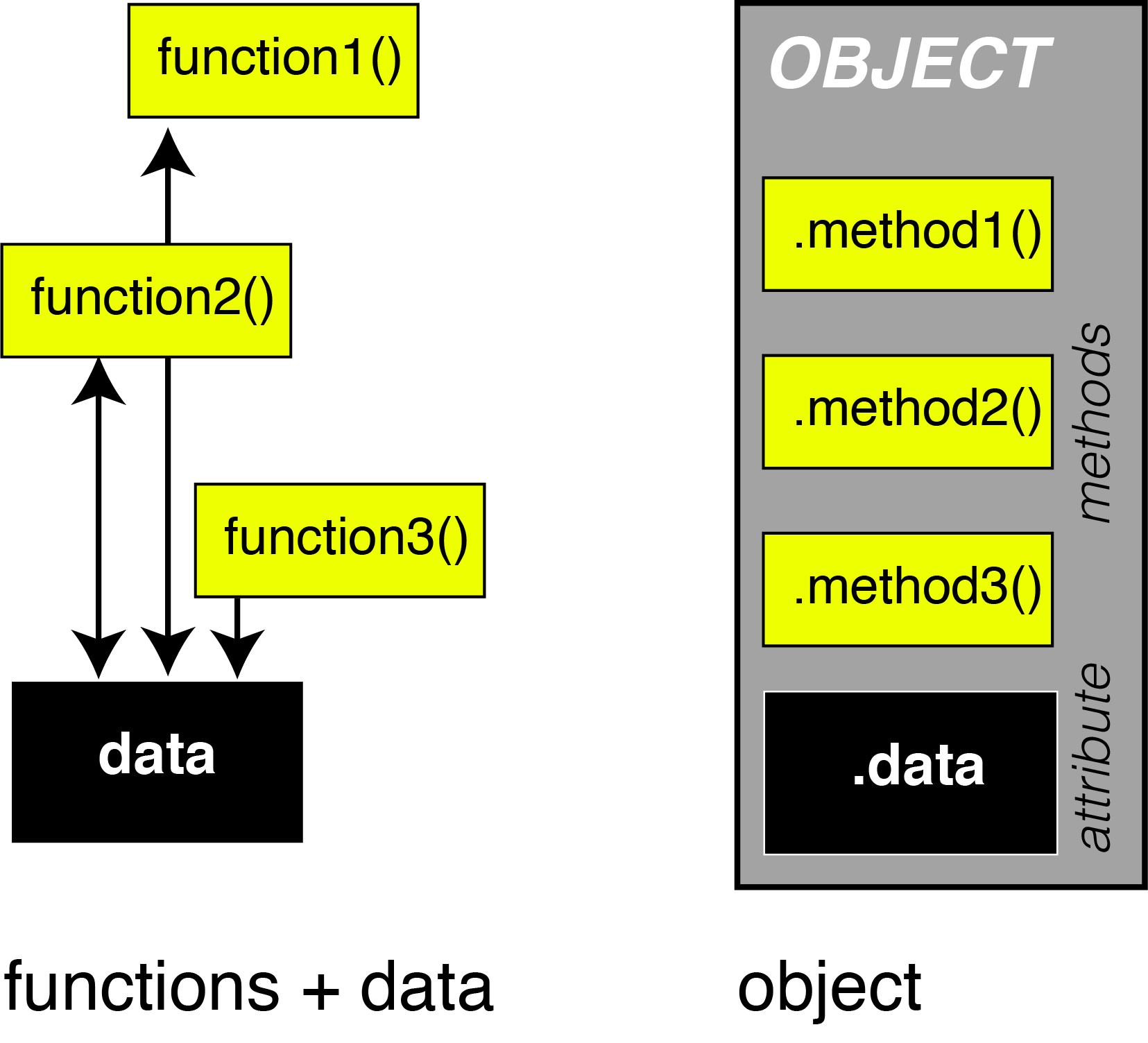

Using functions is the most important way to write scientific code. The basic approach is to have blocks of code that take in data and return results; this is called procedural programming.

But there is also another way in which data and functions are combined into something called an object, which leads to object oriented programming (OOP). An object contains data (held in variables that are called attributes) and it also contains functions (called methods) that know how to operate on the data in the object.

Python is an object oriented (OO) language and objects are everywhere — in fact everything is an object in Python so anything you learn about objects applies to everything in Python.

Pro Tip

Key terms for OOP in Python:

- object: think of it as a data structure together with the code needed to work with this data structure (like a list that can be appended to or sorted and has a length)

- attribute: a “variable” associated with an object, e.g.,

obj.variable1 - method: a “function” associated with an object, e.g.,

obj.func(...) - Attributes and methods are accessed with the dot operation (like the content of modules 2)

In Python one can create an object as an instance of a class; the

classdefinition describes the contents of the object and instantiation (“calling” the class) creates an instance.An instance is the object that you will work with. There can be multiple independent instances of the same class. (Think of the class definition as the blue print or template and the instance as the actual built thingy.)

Some Python objects

Even if you don’t use object-oriented programming, you still need to know how to work with Python objects. We look at a few examples.

Each built-in type (int, float, str, …) is an object with associated methods and attributes.

Strings

The text sequence — or “string” — type str has lots of string methods:3

>>> sentence = "may the force be with you!"

>>> sentence.capitalize()

'May the force be with you!'

>>> sentence.upper()

'MAY THE FORCE BE WITH YOU!'

>>> sentence.count("o")

2

>>> sentence.isdigit()

False

>>> sentence.replace("you", "us")

'may the force be with us!'

>>> sentence.split()

['may', 'the', 'force', 'be', 'with', 'you!']Note that the string object itself contains all these methods:

>>> "may the force be with you!".upper()

'MAY THE FORCE BE WITH YOU!'The output of many of these methods is again a string so one can easily concatenate or “chain” methods:

>>> sentence.replace("you", "us").title()

'May The Force Be With Us!'Pro Tip

If you are curious about other methods of an object such as the string sentences, use the TAB-completion in ipython on the object with a following period . where hitting the <TAB> key twice will bring up the menu of all options:

sentence.<TAB><TAB>This will show you all methods and attributes.

Exercise string methods

Given the sentence "MAY THE FORCE BE WITH YOU!"

- test if it is lower case

- make it lower case

Lists

The list type contains a large number of useful methods that allow one to manipulate the list. Typically, all operations are done “in place”, i.e., they change the list itself.

Exercise Learning list methods

Work through the exercise and observe what happens to the list rebels in order to understand what the different list methods do to the data in the list.

# Episode V - The Empire Strikes Back: Cloud City

# (SPOILER ALERT!)

>>> rebels = ["Leia", "Han", "Chewie", "C3PO"]

>>> print(rebels)

['Leia', 'Han', 'Chewie', 'C3PO']

>>> rebels.append("Lando")

>>> print(rebels)

['Leia', 'Han', 'Chewie', 'C3PO', 'Lando']

>>> rebels.remove("C3PO")

>>> print(rebels)

['Leia', 'Han', 'Chewie', 'Lando']

>>> rebels.pop()

'Lando'

>>> print(rebels)

['Leia', 'Han', 'Chewie']

>>> rebels.insert(2, "C3PO")

>>> print(rebels)

['Leia', 'Han', 'C3PO', 'Chewie']

>>> rebels.remove("Han")

>>> print(rebels)

['Leia', 'C3PO', 'Chewie']

>>> rebels.extend(["R2D2", "Luke"])

>>> print(rebels)

['Leia', 'C3PO', 'Chewie', 'R2D2', 'Luke']

>>> rebels.reverse()

>>> print(rebels)

['Luke', 'R2D2', 'Chewie', 'C3PO', 'Leia']

>>> rebels.sort()

>>> print(rebels)

'C3PO', 'Chewie', 'Leia', 'Luke', 'R2D2']

>>> rebels.clear()

>>> print(rebels)

[]Exercise Applying list methods

- generate a list with all even numbers from -100 to +100

- sum these numbers with

sum()– should be 0 - remove the last number and sum — should be -100

- remove numbers -100 and 50 and sum — should be -50

- extend by -100, 200, -200, and sum — should be -250

- extend by 50

- remove the highest number and sum – should be -400

Creating objects: classes

In Python one creates an object by first defining a class:4

class ClassName:

"""Doc string for the class"""

def __init__(self, a, b, c, d=1, e=None):

"""(optional) initialization method"""

self.a = float(a) # set attributes

self.b = str(b)

...

def method1(self, x):

"""(optional) method with argument x"""

y = x * self.a

return y

def method2(self):

"""(optional) method with no arguments"""

...

The code block of the

classdefinition contains “function” definitions that define the methods of the class.Any data attributes can be set inside methods and they can be initialized in the special

__init__()method that is called on instantiation.- Methods are accessed with the dot operation.

The first argument of each method is special and is called

selfby convention. It is used by Python and is used to refer to the object itself.Note

When calling a method, do not supply

self, only supply the other arguments!Methods can return values with the

returnstatement. If thereturnstatement is ommitted they will still returnNonebut presumably the method is doing something else such as changing the state of the instance or performing I/O.- Data attributes are variables of

selfthat are accessed with the dot operator, e.g.,self.a. - The

__init__()method is special and is used to initialize the instance. One can execute code and set attributes.__init__()does not have areturnstatement.

The class statement defines a new type of object (short: “a new type”).

To create an instance of a class (a useable object of the type ClassName in our example) one must instantiate it:

thingy = ClassName(2.5, "PHY432", ["towel", "babelfish"], d=3.1415e24)

To access an attribute, use the dot operator:

>>> print(thingy.a)

2.5

will print the value of the attribute a, which was set in __init__().

To call a method, use the dot operator to access the method and provide the appropriate arguments (do not include a value for self as this is provide by Python!):

>>> result = thingy.method1(2)

>>> print(result)

5.0

If a method does not have user arguments such as method2() then it would be called without arguments:

>>> thingy.method()

Activity Our own Sphere object

As an example we will create a module bodies with a class Sphere for spherical bodies.

import math

class Sphere:

"""A simple sphere."""

def __init__(self, pos, radius=1):

self.pos = tuple(pos)

self.radius = float(radius)

def volume(self):

return 4/3 * math.pi * self.radius**3

def translate(self, t):

self.pos = tuple(xi + ti for xi, ti in zip(self.pos, t))Because we created our own module, we first have to import our class

from bodies import SphereWe then instantiate the object (creating an instance of the class)

ball = Sphere((0, 0, 10), radius=2)Notes on the class definition above:

__init__()is a special method that is called when the class is instantiated: it is used to populate the object with user-defined values.- The first argument of each method (including

__init__()) is always calledselfand refers to the class itself. - So-called instance attributes are created with

self.ATTRIBUTE_NAME, e.g.,self.pos. - Methods are defined just like ordinary Python functions except that the first argument is

self.

In this example we created an object named ball, which is of type Sphere:

In [3]: type(ball)

Out[3]: __main__.SphereActivity Attributes and Methods

Objects contain data attributes (variables that are associated with the object) and methods (functions that are associated with the object). Attributes and methods are accessed with the “dot” operator. (Within the class definition, attributes and methods are also accessed with the dot-operator but the class itself is referred to as self — this is just the first argument in each method and you should always, always name it “self”.)

In the example, pos and radius are attributes, and can be accessed as ball.pos and ball.radius. For instance, the Sphere object named ball has position

In [4]: ball.pos

Out[4]: (0, 0, 10)

In [5]: ball.radius

Out[5]: 2.0because we provided the pos argument (0, 0, 10) on instantiation. Similarly, we created a ball with radius 2.

One can assign to these attributes as usual, e.g., directly change the position

In [6]: ball.pos = (-5, 0, 0)

In [7]: ball.pos

Out[7]: (-5, 0, 0)The Sphere.volume() method computes the volume of the sphere:

In [8]: ball.volume()

Out[8]: 33.510321638291124The Sphere.translate() method changes the position of the object by adding a translation vector t to Sphere.pos:

In [9]: ball.translate((5, 0, 0))

In [10]: ball.pos

Out[10]: (0, 0, 0)Note that this method did not return any values but it changed the data in Sphere.pos.

Activity Independence of instances

Each instance of a class is independent from the other instances. For example, ball and a new balloon can be moved independently even though we start them at the same position:

In [11]: ball = Sphere((0, 0, 10), radius=2)

In [12]: balloon = Sphere((0, 0, 10), radius=6)

In [13]: ball.pos = (-1, -1, 0)

In [14]: print(ball.pos, balloon.pos)

(-1, -1, 0) (0, 0, 10)Inheritance

New classes can be built on existing classes in such a way that the new class contains the functionality of the existing class. This is called inheritance and is a very powerful way to organize large code bases.

Activity Deriving a Planet from a Sphere

Only a small example is given to illustrate the basic idea: We use our Sphere class to create planets. A planet is (almost) a sphere but it also has a name and a mass: The new Planet class inherits from Sphere by supplying Sphere as an argument to Planet:

class Planet(Sphere):

def __init__(self, name, pos, mass, radius):

self.name = str(name)

self.pos = tuple(pos)

self.mass = float(mass)

self.radius = float(radius)

def density(self):

"""Compute density of the planet"""

return self.mass / self.volume()

# quantities from http://www.wolframalpha.com

# lengths in m and mass in kg

earth = Planet("Earth", (1.4959802296e11 , 0, 0), 5.9721986e24, 6371e3)

print(earth.density())gives 5513 kg/m3 because the Planet class inherited the volume() method from Sphere.

Exercise Moons and Planets

- Put the

Sphereclass into a filebodies.py. - Put the planet class into a file

astronomy.pyand and importSpherefrom bodies. - Create a new class

Moonwith the same functionality as thePlanetclass shown above. - Add an attribute

moonstoPlanetthat is initialized with the optional keyword argumentmoonsand which stores a list ofMooninstances. - Add a method

systemmass()that calculates the total mass of the planet together with all its moons. - Create

- a

Mooninstance for Earth’s moon Luna - a

Planetinstance for Earth withmoon=[luna] - Mars with its two moons Phobos and Deimos You can use WolframAlpha or NASA’s HORIZONS system to obtain data.

- a

- Calculate the total system masses.

- Extend this example…

Final comments on objects

For most of the class you will not need to work with classes, i.e., you do not have to design your programs in an object-oriented manner. However, everything is an object and we will constantly create objects and work with their methods and attributes. For example list.append() is a method of a list object. Even modules are objects and therefore you are using the dot operator to access its contents.

Pro Tip

In ipython you can list all the attributes and methods of an object by typing the object’s name, a dot, and then hitting the TAB key twice. TAB-completion together with the question mark (help) operator is how most programmers quickly learn about Python classes and objects.

Footnotes

You might also hear the variables of an object called “fields” and both fields and methods be called attributes. In Python there actually does not exist a fundamental difference between fields and methods because functions are objects themselves that are stored in a field. Hence it makes sense to think of all of them as attributes of an object. It is however common in Python to use the terminology introduced above, with attributes and methods. ↩

Do not type the standard Python prompt

>>>, it is just shown to distinguish input from output. ↩It is convenient to put the class definition into a separate module, let’s say

bodies.py, and then you can import the class definitions asfrom bodies import SphereThis tends to be more manageable than working interactively and it is an excellent way to modularize code. ↩